Readings for March 6

- Film Clips

- Readings

- 1. Walter White Describes a Lynch Mob (1915)

- 2. Souvenir Postcards of Lynchings in Texas

- 3. Eyewitnesses Recall the Influenza Epidemic of 1918

- 4. A Puerto Rican Describes U.S. Labor Camp Conditions (1918)

- 5. A Reporter Describes the Triangle Factory Fire (1911)

- 6. Margaret Sanger Advocates Birth Control for Women (1916)

Film Clips

- Conclusion to D.W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation (1915) watch

- Excerpt from Coney Island (1917) watch

- Billy Sunday Preaches in Favor of Prohibition and the Eighteenth Amendment watch

Readings

1. Walter White Describes a Lynch Mob (1915)

Please read “The Work of a Mob,” in The Crisis 16, no. 5 (September 1918), pp. 221-223. This article by Walter F. White, assistant secretary of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), describes a recent series of lynchings of African Americans in Georgia.

2. Souvenir Postcards of Lynchings in Texas

The website Without Sanctuary contains an archive of “photographs and postcards taken as souvenirs at lynchings throughout America.” These are disturbing images, only two of which are selected below. The text explaining each photograph is taken from the site, which was created by John Littlefield and James Allen.

Dallas, 1910

Silhouetted corpse of African American Allen Brooks hanging from Elk’s Arch, surrounded by spectators. March 3, 1910. Dallas, Texas. Tinted lithographed postcard. 3 1/2 x 5 1/2 in.

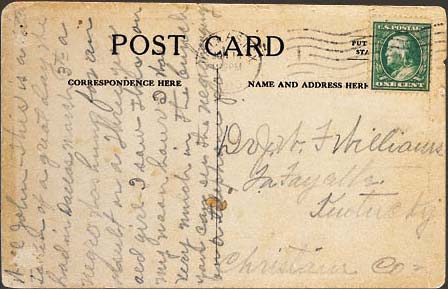

Back of the postcard, with inscription by sender

The Palace Drugstore dominated a prime commercial corner just under one of downtown Dallas’s most prominent architectural landmarks, the soaring Elk’s Arch. Together, they formed a makeshift amphitheater for the last act of the tragic comedy of March 3, 1910; the Palace’s two story facade providing an urban backdrop with box office seats for Elk’s Arch’s dramatic shell. The first incongruous notes that sliced the routine lunchtime din, wafted through the open second-floor windows, drawing the curious and, undoubtedly, alarming a few. Within minutes, the elevated onlookers spotted, in the increasingly agitated streets down below, a man scaling the arch and securing a rope. Then, from off the sullied pavement and over the heads of thousands of riveted Dallasites, the mutilated corpse of a naked, elderly Negro ascended. Audible to some were the words of commendation a mob leader had for his fellow lynchers.

“You did the work of men today and your deeds will resound in every state, village, and hamlet where purity and innocence are cherished and bestiality and lechery condemned.”

The H. J. Buvens family had esteemed Allen Brooks a trusted servant until Flora Daingerfield, a second servant, claimed to have discovered Brooks with their missing three-year old daughter in the barn. Dr. W. W. Brandau examined the child and concluded, rather vaguely, that there was “evidence of brutal treatment.” A local newspaper described the alleged crime as “one of the most heinous since the days of Reconstruction.” Immediately following Brooks arrest, a mob attempted, but failed, to kidnap him from authorities. But while his trial was underway, a second mob, of two hundred whites and one “conspicuous Negro,” entered the courtroom and successfully overwhelmed a “defending force” of fifty armed deputies and twenty policemen.

No shots were fired. The defenseless Brooks was trapped on an upper floor. The mobsters tightened a noose around his neck and threw him down to the hungry pack twenty feet below. Dozens savagely attacked, kicking and crushing his face until he was covered in blood. The adherents of hanging overruled those with a taste for burning. The unholy pilgrimage from courthouse to arch began.

“Contact with the pavement and obstacles on it wore most of the clothes off the Negro before the arch was reached,” noted the Dallas Morning News. “At one point his coat was torn off, at another his shoes were dragged from his feet, and finally his trousers yielded to the friction of the passage along the street.” What remnants of clothing that clung to the corpse were soon stripped away by souvenir hunters.

Postmarked June 11, 1910, Dallas Texas.

Source: http://withoutsanctuary.org/pics_07.html

Waco, Texas, 1916

Spectators at the lynching of Jesse Washington, one man raised for a better view. May 16, 1916, Waco, Texas. Gelatin silver print. Real photo postcard. 5 1/2 x 3 1/2

Washington was a mentally retarded seventeen-year-old boy. On May 8, 1916, lucy Fryer, a white woman, was murdered in Robinson, seven miles from Waco. Washington, a laborer on her farm, confessed to the murder. in a brief trial on May 15, the prosecution had only to present a murder weapon and Washington’s confession. The jury deliberated for four minutes, and the guilty verdict was read to shouts of, “Get that Nigger!”

The boy was beaten and dragged to the suspension bridge spanning the Brazos River. Thousands roared, “Burn him!” Bonfire preparations were already under way in the public square, where Washington was beaten with shovels and bricks. Fifteen thousand men, women, and children packed the square. They climbed up poles and onto the tops of cars, hung from windows, and sat on each other’s shoulders. Children were lifted by their parents into the air. Washington was castrated, and his ears were cut off. A tree supported the iron chain that lifted him above the fire of boxes and sticks. Wailing, the boy attempted to climb the skillet-hot chain. For this the men cut off his fingers. The executioners repeatedly lowered the boy into the flames and hoisted him out again. With each repetition, a mighty shout was raised.

Source: http://withoutsanctuary.org/pics_21.html

3. Eyewitnesses Recall the Influenza Epidemic of 1918

In 1918, a global influenza pandemic hit the United States, killing over 600,000 Americans in about one year’s time. Read these later recollections of those who lived through the pandemic, and click on the Source links if you would like to hear audio clips of their interviews.

Teamus Bartley (Kentucky)

It was the saddest lookin’ time then that ever you saw in your life. My brother lived over there in the camps then and I was working over there and I was dropping cars onto the team pole. And that, that epidemic broke out and people went to dyin’ and there just four and five dyin’ every night dyin’ right there in the camps, every night. And I began goin’ over there, my brother and all his family took down with it, what’d they call it, the flu? Yeah, 1918 flu. And, uh, when I’d get over there I’d ride my horse and, and go over there in the evening and I’d stay with my brother about three hours and do what I could to help ‘em. And every one of them was in the bed and sometimes Doctor Preston would come while I was there, he was the doctor. And he said “I’m a tryin’ to save their lives but I’m afraid I’m not going to.”And they were so bad off. And, and every, nearly every porch, every porch that I’d look at had—would have a casket box a sittin’ on it. And men a diggin’ graves just as hard as they could and the mines had to shut down there wasn’t a nary a man, there wasn’t a, there wasn’t a mine arunnin’ a lump of coal or runnin’ no work. Stayed that away for about six weeks.

Source: http://historymatters.gmu.edu/d/107

Philadelphians Remember the Flu

Clifford Adams: They were stacked up in the cemetery and they couldn’t bury them. I was living on 31st St. then. And that was a two-way street then, you know, and it’s one-way now. But people that died over this way had to be buried over this way and they used to have a funeral procession coming this way. And they used to be crossing. You had, they had to come to this bridge, coming one way or the other. And people would be there. And I would be layin’ in there and I says, I looked out the window and says, “There are two funeral processions. One going one way and one going the other way meeting like that.” And that’s the way it was. There wasn’t a lot of comforts in those days. But it didn’t worry me. I was taking care of myself. What I mean, I wasn’t thinking about it. I wasn’t knowing whether I was going to die or what. I was just figuring it’s got me, and eveything else is going on.

Anna Lavin: The undertaker just ran, I don’t know how many, into their wagon and took them to the cemetery and that was it and had to dig your own grave. I mean, the families had to dig their own graves. Grave diggers were sick and that was the terrible thing.

Anne Van Dyke: They didn’t even bury the people. They found them stuck in garages and everything.

Elizabeth: Yes, oh, it was terrible, the flu.

Van Dyke: You had to go, my mother went and shaved the men and laid them out, thinking that they were going to be buried, you know. They wouldn’t bury ’em. They had so many died that they keep putting them in garages. That garage on Richmond Street. Oh, my gosh, he had a couple of garages full of caskets.

Charlie Hardy: Full of bodies?

Elizabeth: Bodies! On Thompson and Allegheny, Schedpa. He used to get the people and take them out and pile them in the garage. And people smelled something and they notified him. There he’d take the people out of the coffin and put them in the garage and give the coffin to somebody else and got paid for it. He lost his license and all. The smell would knock you, it would run down through the alley, so they caught up with him. People used to die. Oh, they used to die. It was an awful disease.

Louise Apuchase: We were the only family saved from the influenza. The rest of the neighbors all were sick. Now I remember so well, very well, directly across the street from us, a boy about 7, 8 years old died and they used to just pick you up and wrap you up in a sheet and put you in a patrol wagon. So the mother and father screaming. “Let me get a macaroni box.” Before, macaroni, any kind of pasta used to come in these wooden boxes about this long and that high, that 20 lbs. of macaroni fitted in the box. “Please, please, let me put him in the macaroni box. Let me put him in the box. Don’t take him away like that.” And that was it. My mother had given birth to my youngest sister at the time and then, thank God, you know, we survived. But they were taking people out left and right. And the undertaker would pile them up and put them in the patrol wagons and take them away.

Source: http://historymatters.gmu.edu/d/13

Loretta Jarussi (Montana)

People would come along, and young men, nineteen, twenty years old, they’d come along and take their [inaudible]. [Sister: They were hauling wheat to Columbus, you know, they were the war years.] And they’d stop and say hello to us. My mother was very friendly. She loved to see those people. She was kind of lonesome there, you know, just us kids and her. So when anybody passed by, she always stayed with them. And, you know, maybe a week later, they’d say so-and-so died, and they had been past our place. So many people had that flu, and young people, and they died.

And, you know, my father contracted that flu, and everybody in the family had it except my mother. And he was in and out of the hospital. He had a shoe shop in Columbus at that time, and he was in and out of the hospital, and he’d go to the hospital and they’d tell him, “There’s nothing wrong with you,” and he’d go. And then he’d come back to the hospital. He just didn’t feel right. He went through that for a number of times. And he finally decided he was going to go to Thermopolis to the springs. He thought going there would help him. And just before he was leaving, he went to the doctor. Dr. Gardner was the doctor at that time, his doctor. And he said, “Dr. Gardner, I’m going to try and go to the springs and see if that helps me.” And he said, “Well, Louie, it might help you.” So while he was there, Dr. Gardner’s son, who also was a doctor, happened to be in there, and he had been in the Army, an Army doctor, and was home on leave, I think. He said, “Dad, if you let that man go to the springs, he’ll come home in a box.” And he said, “Well, what would you suggest?” And he said, “I’ll tell you what we did in the Army,” and it seemed to work. They had a powerful medicine. I don’t know what it was. But he said, “We gave them doses of this medicine, and that seemed to help.”So he gave him this prescription and told him to get it filled, and he said, “Now it’s going to be pretty rough on you. You be sure to tell your wife to use a lot of blankets, wool blankets on you, and as you perspire, to change those blankets and keep you real warm.”

So dad went home and told mom, and mom said, “Okay. Let’s get things going.” And he took a dose of medicine, and it seemed to help a little bit. Then time for a second dose. That also seemed to help. Then he had the third dose, and at that time he thought he was going to die. And he called all the kids around the bed and said, “This is for you, and you’re supposed to do this, and this is yours,” and then he kind of went into—I don’t know—a sleep, a coma. [Sister: It wouldn’t be a coma.] A sleep, a deep sleep. And mama thought, she really did, he had died, but he came out of it, and he felt better. But it took two years to get over that.

Source: http://historymatters.gmu.edu/d/14

4. A Puerto Rican Describes U.S. Labor Camp Conditions (1918)

RAFAEL F. MARCHAN, being first duly sworn, deposes and says: That he is a native of Porto Rico, and a citizen of the United States, twenty-seven years old, married, and temporarily residing at Camp Bragg, Fayettsville, North Carolina; that he, and some other 1700 Porto Ricans, were induced and persuaded, directly or indirectly, by Mr. F.C. Roberts, Special Agent, Bureau of Immigration, Department of Labor, to come, and did come, to this country for the purpose of cooperating within the scope of their respective ability, in the noble task of carrying on this war to a successful issue, by contributing their labor to American industries and works, it being distinctly and clearly understood at the time, that he, the affiant, RAFAEL F. MARCHAN, and the other Porto Ricans, as aforesaid, came under the aegis and protection of the Government, and that he and they were to be employed in their respective trades or such occupations as they were fit for; that it was equally and specifically understood at the said time also that the housing accommodations and living and working conditions were to be of such a kind as to insure their health and comfort, and that proper measures would be taken to provide for their welfare and protection against mistreatment and abuse while employed in such work as aforesaid; that it was further understood that the said affiant and the other Porto Ricans as aforesaid, were to be sent to such States of the Union as are farthest south, where the climate and general conditions are more similar to those under which they have been accustomed to live and work. It was also understood that if any or all of the said Porto Ricans should not be satisfied with working or living conditions or should merely wish to change to some other work for which he or they were competent or fit for or to some other place of his or their choosing, he or they could do so, and that they were not to be restrained in their personal liberty or in any way compelled to do any kind of work or live in any given place against their will.

The affiant, RAFAEL F. MARCHAN, further deposes and says, that he and the other Porto Ricans as aforesaid were brought from Porto Rico to this country in the Government Transport City of Savannah, through the port of Wilmington, Delaware, whence they were brought to Camp Bragg, at Fayettsville, North Carolina, on September 29, 1918, where they were housed in improperly constructed barracks without protection from the cold weather; that so far as he can make out they were turned over to James Stewart and Company, Inc., Contractors for the construction of the said Camp, to work for them under conditions and terms wholly unsatisfactory to them, the said affiant and the other Porto Ricans as aforesaid, who, without any distinction or discrimination as to capacity or qualifications, were on the next and successive days ordered to clear the grounds of timber and brush for the Camp, with the exception of a few of them who were detailed to hospitals, offices, etc.

The affiant, RAFAEL F. MARCHAN, further deposes and says, that owing to the improper and unsanitary conditions under which the said Porto Ricans labor and live at the said Camp Bragg their health and comfort and even their lives are not only endangered and put in jeopardy but actually broken up and destroyed as it has been the case with some twenty-two of them who have died from utter lack of proper care and medical attention. And the affiant says that at the Hospital the same drinking glass and other utensils are indiscriminately used by all without previous disinfection, with the resulting infection and contagion of such dreaded diseases as influenza, consumption, pneumonia, etc.; and the affiant further says that there have been cases of such utter and inhuman cruelty as to compel sick men under the pretext of their being lazy, to either go to work or be locked up, just because in fear of the ill treatment which they expected to receive at the hospital they would rather stay in their own beds, and when the men are sent to the hospital they are not always sure they will not be neglected and abused without any consideration or regard for their condition; and the affiant further says that there was a case of such apparent neglect and criminal negligence as to permit a man to die from a wound on his foot which was infected and aggravated by the first aid bandage which was put on it and never removed for about a week until he passed away; and that there was a notorious case of abuse of a sick man in the hospital who was ordered from his bed by the attending physician and when he would not do it as quickly as ordered, the said attending physician took him by the arm and violently threw him out of bed upon the floor. And the affiant further says that men are put to bed at the hospital with their working clothes on, that they all are given no other medicine or treatment than some “white tablets” which have become a sort of a joke among the Porto Ricans as being considered a sort of omnipresent cure-all or universal panacea for all ailments, from a simple cold to sore feet, pneumonia or rheumatism; and that the same holds true as to diet there being no difference made in this respect as between the very sick and those slightly ill.

The affiant, RAFAEL F. MARCHAN, further deposes and says, that these Porto Ricans are compelled to use mess books which are obtained at the office, and when men working far away from the said office arrive there a little late they are told to go without food because the man in charge is generally in a hurry to close up and go to town for the night, usually making some remark or excuse such as that there are no more mess books left, or that office hours are over, etc.; and the affiant says that at one time when a number of men went to work to some particular place a little ways off from the regular mess halls, they were compelled by force at the point of revolvers to take some food which they did not want because it was not satisfactory, and prevented from going to the regular mess halls, where they would prefer to go for their dinner, and those who resisted this outrageous imposition were violently pushed about and abused, and one was quite badly injured; and the affiant further says that at these regular mess halls they serve only one kind of food and if any of the men wishes to have something else within reason, such as a glass of milk, a couple of eggs or a piece of pie, etc., they are met with the invariable remark that they can not have it. And the affiant further says that, in exchange, those at the office can have most anything they wish while they pay exactly the same price for their food as the common laborers who must be contented to accept what they can get, to their detriment and with evident injustice to them.

And the affiant further deposes and says, that as illustrating the general treatment accorded these Porto Ricans at the Camp, there have been such cases of outrageous unspeakable abuse and degrading ill treatment of the men that some have positively refused to continue at the Camp and announced their intention to leave, but have been prevented to do so by sheer compulsion of force, thus being deprived of their liberty and what is still worse compelled to remain in a state of involuntary servitude; and the affiant says, that even the Fire Chief, who evidently is a regular bully at the Camp has gone so far outside the scope of his authority at different occasions that the men under him are wont to look upon him as the terror of the place, the bulldog of the Camp, who has no hesitation in striking men with his fist or brandish his revolver in their faces; and the affiant further says that the acts of cruelty committed daily against these men are too numerous to be cited here in all their repulsive and disgusting details; that as illustrative of the callousness and heartlessness of the treatment accorded to these people by some of the men in authority at the Camp the case may be cited of a poor old man who was inhumanely knocked down and made to cry by one of these fiendish individuals who afterwards, finding him asleep near the same spot where he was knocked down, set fire to the dried leaves and twigs around his helpless form in order to frighten the old man, making him believe that he was to be burned alive.

And the affiant further deposes and says that he has been instructed by a number of these Porto Ricans to lay before the Commissioner of Porto Rico their grievances with the request that the matter be taken up with the proper authorities of the Government with a view to have the proper remedy applied to a situation which has become unbearable; and the affiant says that the said petition to said Commissioner was not subscribed by all of the men, because it has to be done under secrecy in order to avoid detection at the Camp by those interested in having all these shameful things ignored and kept from the general public and the Government of the United States, even at the cost of further and greater crimes against them.

(signed) Rafael F. Marchan

Subscribed and sworn to before me this 24th day of October, 1918. (signed) illegible

Notary Public D.C.

Source: “Rafael Marchan Statement,” October 24, 1918 in: Record of the Bureau of Insular Affairs, Record Group 350, File 1493, (Washington, D.C.:National Archives), pp. 123–126. Reproduced here from History Matters

5. A Reporter Describes the Triangle Factory Fire (1911)

United Press reporte William Sheperd was on the scene in New York City in 1911 when a factory run by the Triangle Shirtwaist Company caught fire, resulting in the deaths of 146 workers inside, most of them women.

I was walking through Washington Square when a puff of smoke issuing from the factory building caught my eye. I reached the building before the alarm was turned in. I saw every feature of the tragedy visible from outside the building. I learned a new sound–a more horrible sound than description can picture. It was the thud of a speeding, living body on a stone sidewalk.

Thud-dead, thud-dead, thud-dead, thud-dead. Sixty-two thud-deads. I call them that, because the sound and the thought of death came to me each time, at the same instant. There was plenty of chance to watch them as they came down. The height was eighty feet.

The first ten thud-deads shocked me. I looked up-saw that there were scores of girls at the windows. The flames from the floor below were beating in their faces. Somehow I knew that they, too, must come down, and something within me-something that I didn’t know was there-steeled me.

I even watched one girl falling. Waving her arms, trying to keep her body upright until the very instant she struck the sidewalk, she was trying to balance herself. Then came the thud–then a silent, unmoving pile of clothing and twisted, broken limbs.

As I reached the scene of the fire, a cloud of smoke hung over the building. . . . I looked up to the seventh floor. There was a living picture in each window-four screaming heads of girls waving their arms.

“Call the firemen,” they screamed-scores of them. “Get a ladder,” cried others. They were all as alive and whole and sound as were we who stood on the sidewalk. I couldn’t help thinking of that. We cried to them not to jump. We heard the siren of a fire engine in the distance. The other sirens sounded from several directions.

“Here they come,” we yelled. “Don’t jump; stay there.”

One girl climbed onto the window sash. Those behind her tried to hold her back. Then she dropped into space. I didn’t notice whether those above watched her drop because I had turned away. Then came that first thud. I looked up, another girl was climbing onto the window sill; others were crowding behind her. She dropped. I watched her fall, and again the dreadful sound. Two windows away two girls were climbing onto the sill; they were fighting each other and crowding for air. Behind them I saw many screaming heads. They fell almost together, but I heard two distinct thuds. Then the flames burst out through the windows on the floor below them, and curled up into their faces.

The firemen began to raise a ladder. Others took out a life net and, while they were rushing to the sidewalk with it, two more girls shot down. The firemen held it under them; the bodies broke it; the grotesque simile of a dog jumping through a hoop struck me. Before they could move the net another girl’s body flashed through it. The thuds were just as loud, it seemed, as if there had been no net there. It seemed to me that the thuds were so loud that they might have been heard all over the city.

I had counted ten. Then my dulled senses began to work automatically. I noticed things that it had not occurred to me before to notice. Little details that the first shock had blinded me to. I looked up to see whether those above watched those who fell. I noticed that they did; they watched them every inch of the way down and probably heard the roaring thuds that we heard.

As I looked up I saw a love affair in the midst of all the horror. A young man helped a girl to the window sill. Then he held her out, deliberately away from the building and let her drop. He seemed cool and calculating. He held out a second girl the same way and let her drop. Then he held out a third girl who did not resist. I noticed that. They were as unresisting as if he were helping them onto a streetcar instead of into eternity. Undoubtedly he saw that a terrible death awaited them in the flames, and his was only a terrible chivalry.

Then came the love amid the flames. He brought another girl to the window. Those of us who were looking saw her put her arms about him and kiss him. Then he held her out into space and dropped her. But quick as a flash he was on the window sill himself. His coat fluttered upward-the air filled his trouser legs. I could see that he wore tan shoes and hose. His hat remained on his head.

Thud-dead, thud-dead-together they went into eternity. I saw his face before they covered it. You could see in it that he was a real man. He had done his best.

We found out later that, in the room in which he stood, many girls were being burned to death by the flames and were screaming in an inferno of flame and heat. He chose the easiest way and was brave enough to even help the girl he loved to a quicker death, after she had given him a goodbye kiss. He leaped with an energy as if to arrive first in that mysterious land of eternity, but her thud-dead came first.

The firemen raised the longest ladder. It reached only to the sixth floor. I saw the last girl jump at it and miss it. And then the faces disappeared from the window. But now the crowd was enormous, though all this had occurred in less than seven minutes, the start of the fire and the thuds and deaths.

I heard screams around the corner and hurried there. What I had seen before was not so terrible as what had followed. Up in the [ninth] floor girls were burning to death before our very eyes. They were jammed in the windows. No one was lucky enough to be able to jump, it seemed. But, one by one, the jams broke. Down came the bodies in a shower, burning, smoking-flaming bodies, with disheveled hair trailing upward. They had fought each other to die by jumping instead of by fire.

The whole, sound, unharmed girls who had jumped on the other side of the building had tried to fall feet down. But these fire torches, suffering ones, fell inertly, only intent that death should come to them on the sidewalk instead of in the furnace behind them.

On the sidewalk lay heaps of broken bodies. A policeman later went about with tags, which he fastened with wires to the wrists of the dead girls, numbering each with a lead pencil, and I saw him fasten tag no. 54 to the wrist of a girl who wore an engagement ring. A fireman who came downstairs from the building told me that there were at least fifty bodies in the big room on the seventh floor. Another fireman told me that more girls had jumped down an air shaft in the rear of the building. I went back there, into the narrow court, and saw a heap of dead girls. . . .

The floods of water from the firemen’s hose that ran into the gutter were actually stained red with blood. I looked upon the heap of dead bodies and I remembered these girls were the shirtwaist makers. I remembered their great strike of last year in which these same girls had demanded more sanitary conditions and more safety precautions in the shops. These dead bodies were the answer.

Source: William Shepherd Testimonial on The 1911 Triangle Factory Fire Exhibit at Cornell University

6. Margaret Sanger Advocates Birth Control for Women (1916)

This article by Sanger on “‘The Woman Rebel’ and the Fight for Birth Control” is taken from Records of the Joint Legislative Committee to Investigate Seditious Activities, New York State Archives, Margaret Sanger Microfilm C16:1035.

During fourteen years experience as a trained nurse, I found that a great percentage of women’s diseases were due to ignorance of the means to prevent conception. I found that quackery was thriving on this ignorance, and that thousands of abortions were being performed each year– principally upon the women of the working class. Since the laws deter reliable and expert surgeons from performing abortions, working women have always been thrown into the hands of the incompetent, with fatal results. The deaths from abortions mount very high.

I found that physicians and nurses were dealing with these symptoms rather than their causes, and I decided to help remove the chief cause by imparting knowledge to prevent conception, in defiance of existing laws and their extreme penalty. I sent out a call to the proletarian women of America to assist me in this work, and their answers came by the thousands. I started The Woman Rebel early in 1914. The first issue of the magazine was suppressed. Seven issues out of nine were suppressed, and although sent out as first-class mail, the editions were confiscated. The newspapers–even the most radical– declined to give this official tyranny any publicity.

In August, 1914, a Federal Grand Jury returned three indictments against me, based on articles in the March, May and July issues of The Woman Rebel. The articles branded as “obscene” merely discussed the question and contained no information how to prevent conception. But the authorities were anxious to forestall the distribution of this knowledge and knew that this could only be done by imprisoning me. I decided to avoid the imprisonment, at least until I had given out the information. One hundred thousand copies of a pamphlet, Family Limitation, were prepared and distributed, and I sailed for England.

I studied the question in England, Holland, France and Spain, and prepared three other pamphlets: English Methods of Birth Control, Dutch Methods of Birth Control, and Magnetation Methods of Birth Control.

After these had been mailed to the United States, I returned to take up the fight with the authorities. The latter had, in the meantime, set a Comstock trap for William Sanger and railroaded him to jail for 30 days. Nevertheless they postponed my case time and again, although I was anxious to face the issue and get the decision of a jury. They noted the widespread agitation in favor of birth control. They saw that interest had been thoroughly aroused. Never had there been an issue that had so aroused the entire country. Letters at the rate of 40 to 50 a day poured in upon the authorities and educated them.

Finally, it was decided by Federal Judge Dayton, United States District Attorney Marshall and Assistant United States District Attorney Content to acquit me, instead of allowing a jury to do it. This decision is fully as important a precedent for future work as the decision of a jury would have been.

Hundreds of requests have been made to me to revive The Woman Rebel; but I feel that it has already accomplished its purpose–to arouse interest. Now more constructive work is needed, in meeting the people directly and interesting them in establishing free clinics in those sections where women are overburdened with large families.

MARGARET SANGER, 163 Lexington Avenue, New York, N.Y.