Readings for March 13

- Film Clip

- Readings

- 1. A Description of the Anthropology Building at the World’s Fair of 1893

- 2. Ida B. Wells and Frederick Douglass Criticize the World’s Fair (1893)

- 3. Booker T. Washington Advocates Industrial Education (1896)

- 4. W. E. B. DuBois Criticizes Booker T. Washington (1903)

- 5. A Report of the Homestead Strike of 1892

- 6. Text of the Geary Act of 1892

- 7. Instructions for the Celebration of Columbus Day (1892)

Film Clip

In 1893, to mark the 400th anniversary of the putative discovery of the New World by Christopher Columbus, Chicago hosted the World’s Columbian Exposition.

Part amusement park, part architectural exhibit, and part mini-city, the “World’s Fair,” as it was also known, attracted almost 30 million visitors while its doors were open. It featured exhibits on technological inventions, history, agriculture, anthropology and much more.

The Urban Simulation Team at UCLA has been building a full-scale virtual model of the Columbian Exposition, using documents from the time to reconstruct specific exhibits. Before reading the texts below, try walking through the Street in Cairo exhibit. (Note: This link points to a WMV video file. If you have a Mac and clicking doesn’t work, you may need to install software like the VLC Media Player to view the movie.)

Readings

1. A Description of the Anthropology Building at the World’s Fair of 1893

Chapter 20 from Hubert Howe Bancroft’s The Book of the Fair (Chicago, 1893).

Least pretentious among the structures of the Fair in which are housed its main exhibits is the Anthropological building, where is presented a record in miniature of man’s condition, progress and achievement, from prehistoric eras to the days in which we live. In this department are several divisions and many sub-divisions, first among which are archaeology and ethnology, with their various branches. In the former section, beginning with the stone age, are shown portions of human skeletons and specimens of handiwork unearthed from geologic strata, from mounds and shell heaps, from caves and burial places, from the ruins of ancient cities and pueblos, and in a word from every portion of the New World where its ancient races have left their impress. From the valleys of the Ohio and Mississippi, and elsewhere to the borders of either ocean, from Mexico and Central and South America have been unearthed, after the lapse of unnumbered aions, their buried implements of stone, iron, or copper, their household utensils and ornaments, and whatever else may serve to throw light on the paleolithic and other prehistoric periods. Some of the exhibits are arranged in geographical groupings, as the models of cliff dwellings from Colorado, New Mexico, and Arizona, and of the sculptured ruins of Copan.

For those who incline to this field of investigation, a section is devoted to physical anthropology. Here, in the skulls, charts, diagrams, and models gathered from many nations, may be compared the past and present types of the human race. There are the skulls of the ancient Greek, Italian, German, and Helvetian; there are the skulls of savages and apes; there are casts of faces typical of tribes and nationalities; there are diagrams showing the comparative stature and anatomical measurement of men and women in various countries, with photographs, statues, and other appliances for a thorough study of this important branch of science. Elsewhere by similar agencies are illustrated the functions and activities of the brain and the organs of sense, whether in normal or in unhealthy condition. In the case of children there are also apparatus for an experimental study of mental phenomena, the subjects being chosen from those who would submit themselves to certain tests while visiting this department of the Fair.

A special and most interesting section has for its subjects primitive religions, folk-lore, and games, the last being grouped together so as to form a comparative study. But it is on the exhibits relating to the condition and progress of man that the interest mainly centres, and especially on such as pertain to modern man; for from the relics of the buried past, whose history at best is largely diluted with speculation, we turn with a sense of relief to more practical evidences of his achievements as contained in written or printed page. Thus is has been the prime object of the ethnological display to afford an opportunity for the study of national types, not only from a scientific point of view, but as far as possible through living specimens. To this end a strong background has been obtained by placing before the spectator the representatives of races existing on this continent in the days of the Columbian era. Then are illustrated special epochs and events, with portraits and busts of those of whose lives and achievements our history largely consists, but without allusion to the annals of the civil war, a theme entirely out of place in an exposition devoted to the arts of peace. …

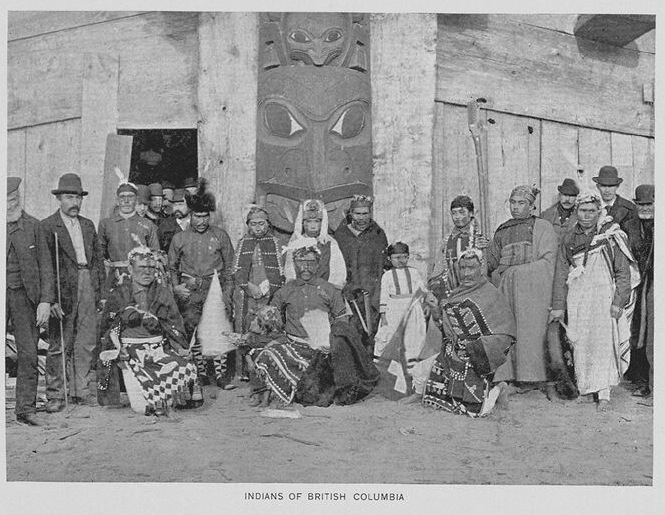

Photograph of one of ethnological displays of “living specimens” in the Anthropology Department, featuring “Indians from British Columbia”

Source: The Book of the Fair hyptertext edition at the Illinois Institute of Technology

2. Ida B. Wells and Frederick Douglass Criticize the World’s Fair (1893)

These excerpts are taken from the pamphlet The Reason Why the Colored American is Not in the World’s Columbian Exposition (Chicago, Ida B. Wells, 1893). The preface was written by the anti-lynching crusader Ida B. Wells, an African American woman.

PREFACE

TO THE SEEKER AFTER TRUTH

Columbia has bidden the civilized world to join with her in celebrating the four-hundredth anniversary of the discovery of America, and the invitation has been accepted. At Jackson Park are displayed exhibits of her natural resources, and her progress in the arts and sciences, but that which would best illustrate her moral grandeur has been ignored.

The exhibit of the progress made by a race in 25 years of freedom as against 250 years of slavery, would have been the greatest tribute to the greatness and progressiveness of American institutions which could have been shown the world. The colored people of this great Republic number eight millions – more than one-tenth the whole population of the United States. They were among the earliest settlers of this continent, landing at Jamestown, Virginia in 1619 in a slave ship, before the Puritans, who landed at Plymouth in 1620. They have contributed a large share to American prosperity and civilization. The labor of one-half of this country has always been, and is still being done by them. The first crédit this country had in its commerce with foreign nations was created by productions resulting from their labor. The wealth created by their industry has afforded to the white people of this country the leisure essential to their great progress in education, art, science, industry and invention.

Those visitors to the World’s Columbian Exposition who know these facts, especially foreigners will naturally ask: Why are not the colored people, who constitute so large an element of the American population, and who have contributed so large a share to American greatness, more visibly present and better represented in this World’s Exposition? Why are they not taking part in this glorious celebration of the four-hundredth anniversary of the discovery of their country? Are they so dull and stupid as to feel no interest in this great event? It is to answer these questions and supply as far as possible our lack of representation at the Exposition that the Afro-American has published this volume. …

INTRODUCTION

BY FREDERICK DOUGLASS

The colored people of America are not indifferent to the good opinion of the world, and we have made every effort to improve our first years of freedom and citizenship. We earnestly desired to show some results of our first thirty years of acknowledged manhood and womanhood. Wherein we have failed, it has been not our fault but our misfortune, and it is sincerely hoped that this brief story, not only of our successes, but of trials and failures, our hopes and disappointments will relieve us of the charge of indifference and indolence. We have deemed it only a duty to ourselves, to make plain what might otherwise be misunderstood and misconstrued concerning us. To do this we must begin with slavery. The duty undertaken is far from a welcome one.

It involves the necessity of plain speaking of wrongs and outrages endured, and of rights withheld, and withheld in flagrant contradiction to boasted American Republican liberty and civilization. It is always more agreeable to speak well of one’s country and its institutions than to speak otherwise; to tell of their good qualities rather than of their evil ones.

There are many good things concerning our country and countrymen of which we would be glad to tell in this pamphlet, if we could do so, and at the same time tell the truth. We would like for instance to tell our visitors that the moral progress of the American people has kept even pace with their enterprise and their material civilization; that practice by the ruling class has gone on hand in hand with American professions; that two hundred and sixty years of progress and enlightenment have banished barbarism and race hate from the United States; that the old things of slavery have entirely passed away, and that all things pertaining to the colored people have become new; that American liberty is now the undisputed possession of all the American people: that American law is now the shield alike of black and white; that the spirit of slavery and class domination has no longer any lurking place in any part of this country; that the statement of human rights contained in its glorious Declaration of Independence, including the right to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness is not an empty boast nor a mere rhetorical flourish, but a soberly and honestly accepted truth, to be carried out in good faith; … that here Negroes are not tortured, shot, hanged or burned to death, merely on suspicion of crime and without ever seeing a judge, a jury or advocate; … that the National Government is not a rope of sand, but has both the power and the disposition to protect the lives and liberties of American citizens of whatever color, at home, not less than abroad; that it will send its men-of-war to chastise the murder of its citizens in New Orleans or in any other part of the south, as readily as for the same purpose it will send them to Chili, Hayti or San Domingo; … that this World’s Columbian Exposition, with its splendid display of wealth and power, its triumphs of art and its multitudinous architectural and other attractions, is a fair indication of the elevated and liberal sentiment of the American people, and that to the colored people of America, morally speaking, the World’s Fair now in progress, is not a whited sepulcher.

All this, and more, we would gladly say of American laws, manners, customs and Christianity. But unhappily, nothing of all this can be said, without qualification and without flagrant disregard of the truth. The explanation is this: We have long had in this country, a system of iniquity which possessed the power of blinding the moral perception, stifling the voice of conscience, blunting all human sensibilities and perverting the plainest teaching of the religion we have here professed, a system which John Wesley truly characterized as the sum of all villanies, and one in view of which Thomas Jefferson, himself a slaveholder, said he “trembled for his country” when he reflected “that God is just and that His justice cannot sleep forever.” That system was American slavery. Though it is now gone, its asserted spirit remains. …

But I need not elaborate the legal and practical definition of slavery. What I have aimed to do, has not only been to show the moral depths, darkness and destitution from which we are still emerging, but to explain the grounds of the prejudice, hate and contempt in which we are still held by the people, who for more than two hundred years doomed us to this cruel and degrading condition. So when it is asked why we are excluded from the World’s Columbian Exposition, the answer is Slavery. …

The life of a Negro slave was never held sacred in the estimation of the people of that section of the country in the time of slavery, and the abolition of slavery against the will of the enslavers did not render a slave’s life more sacred. Such a one could be branded with hot irons, loaded with chains, and whipped to death with impunity when a slave. It only needed be said that he or she was impudent or insolent to a white man, to excuse or justify the killing of him of her. The people of the south are with few exceptions but slightly improved in their sentiments towards those they once held as slaves. The mass of them are the same to-day that they were in the time of slavery, except perhaps that now they think they can murder with a decided advantage in point of economy. In the time of slavery if a Negro was killed, the owner sustained a loss of property. Now he is not restrained by any fear of such loss. …

It must be admitted that, to outward seeming, the colored people of the United States have lost ground and have met with increased and galling resistance since the war of the rebellion. …

It has nevertheless been found impossible to defeat them entirely and to relegate colored citizens to their former condition. They are still free.

Source: http://digital.library.upenn.edu/women/wells/exposition/exposition.html

3. Booker T. Washington Advocates Industrial Education (1896)

From “The Awakening of the Negro” by Booker T. Washington, in the Atlantic Monthly (1896).

When a mere boy, I saw a young colored man, who had spent several years in school, sitting in a common cabin in the South, studying a French grammar. I noted the poverty, the untidiness, the want of system and thrift, that existed about the cabin, notwithstanding his knowledge of French and other academic subjects. Another time, when riding on the outer edges of a town in the South, I heard the sound of a piano coming from a cabin of the same kind. Contriving some excuse, I entered, and began a conversation with the young colored woman who was playing, and who had recently returned from a boarding-school, where she had been studying instrumental music among other things. Despite the fact that her parents were living in a rented cabin, eating poorly cooked food, surrounded with poverty, and having almost none of the conveniences of life, she had persuaded them to rent a piano for four or five dollars per month. Many such instances as these, in connection with my own struggles, impressed upon me the importance of making a study of our needs as a race, and applying the remedy accordingly.

Some one may be tempted to ask, Has not the negro boy or girl as good a right to study a French grammar and instrumental music as the white youth? I answer, Yes, but in the present condition of the negro race in this country there is need of something more. Perhaps I may be forgiven for the seeming egotism if I mention the expansion of my own life partly as an example of what I mean. My earliest recollection is of a small one-room log hut on a large slave plantation in Virginia. After the close of the war, while working in the coal-mines of West Virginia for the support of my mother, I heart in some accidental way of the Hampton Institute. When I learned that it was an institution where a black boy could study, could have a chance to work for his board, and at the same time be taught how to work and to realize the dignity of labor, I resolved to go there. Bidding my mother good-by, I started out one morning to find my way to Hampton, though I was almost penniless and had no definite idea where Hampton was. By walking, begging rides, and paying for a portion of the journey on the steam-cars, I finally succeeded in reaching the city of Richmond, Virginia. I was without money or friends. I slept under a sidewalk, and by working on a vessel next day I earned money to continue my way to the institute, where I arrived with a surplus of fifty cents. At Hampton I found the opportunity–in the way of buildings, teachers, and industries provided by the generous–to get training in the class-room and by practical touch with industrial life, to learn thrift, economy, and push. I was surrounded by an atmosphere of business, Christian influence, and a spirit of self-help that seemed to have awakened every faculty in me, and caused me for the first time to realize what it meant to be a man instead of a piece of property.

While there I resolved that when I had finished the course of training I would go into the far South, into the Black Belt of the South, and give my life to providing the same kind of opportunity for self-reliance and self-awakening that I had found provided for me at Hampton. My work began at Tuskegee, Alabama, in 1881, in a small shanty and church, with one teacher and thirty students, without a dollar’s worth of property. The spirit of work and of industrial thrift, with aid from the State and generosity from the North, has enabled us to develop an institution of eight hundred students gathered from nineteen States, with seventy-nine instructors, fourteen hundred acres of land, and thirty buildings, including large and small; in all, property valued at $280,000. Twenty-five industries have been organized, and the whole work is carried on at an annual cost of about $80,000 in cash; two fifths of the annual expense so far has gone into permanent plant.

What is the object of all this outlay? First, it must be borne in mind that we have in the South a peculiar and unprecedented state of things. It is of the utmost importance that our energy be given to meeting conditions that exist right about us rather than conditions that existed centuries ago or that exist in countries a thousand miles away. What are the cardinal needs among the seven millions of colored people in the South, most of whom are to be found on the plantations? Roughly, these needs may be stated as food, clothing, shelter, education, proper habits, and a settlement of race relations. The seven millions of colored people of the South cannot be reached directly by any missionary agency, but they can be reached by sending out among them strong selected young men and women, with the proper training of head, hand, and heart, who will live among these masses and show them how to lift themselves up. …

Having been fortified at Tuskegee by education of mind, skill of hand, Christian character, ideas of thrift, economy, and push, and a spirit of independence, the student is sent out to become a centre of influence and light in showing the masses of our people in the Black Belt of the South how to lift themselves up. …

The negro has within him immense power for self-uplifting, but for years it will be necessary to guide and stimulate him. …

Nothing else so soon brings about right relations between the two races in the South as the industrial progress of the negro. Friction between the races will pass away in proportion as the black man, by reason of his skill, intelligence, and character, can produce something that the white man wants or respects in the commercial world. This is another reason why at Tuskegee we push the industrial training. We find that as every year we put into a Southern community colored men who can start a brick-yard, a sawmill, a tin-shop, or a printing-office,–men who produce something that makes the white man partly dependent upon the negro, instead of all the dependence being on the other side,–a change takes place in the relations of the races.

Source: http://xroads.virginia.edu/~hyper/WASHINGTON/awakening.html

4. W. E. B. DuBois Criticizes Booker T. Washington (1903)

From The Souls of Black Folk (1903)

Easily the most striking thing in the history of the American Negro since 1876 is the ascendancy of Mr. Booker T. Washington. It began at the time when war memories and ideals were rapidly passing; a day of astonishing commercial development was dawning; a sense of doubt and hesitation overtook the freedmen’s sons,—then it was that his leading began. Mr. Washington came, with a single definite programme, at the psychological moment when the nation was a little ashamed of having bestowed so much sentiment on Negroes, and was concentrating its energies on Dollars. His programme of industrial education, conciliation of the South, and submission and silence as to civil and political rights, was not wholly original; the Free Negroes from 1830 up to wartime had striven to build industrial schools, and the American Missionary Association had from the first taught various trades; and Price and others had sought a way of honorable alliance with the best of the Southerners. But Mr. Washington first indissolubly linked these things; he put enthusiasm, unlimited energy, and perfect faith into this programme, and changed it from a by-path into a veritable Way of Life. And the tale of the methods by which he did this is a fascinating study of human life.

It startled the nation to hear a Negro advocating such a programme after many decades of bitter complaint; it startled and won the applause of the South, it interested and won the admiration of the North; and after a confused murmur of protest, it silenced if it did not convert the Negroes themselves. …

Among his own people, however, Mr. Washington has encountered the strongest and most lasting opposition, amounting at times to bitterness, and even to-day continuing strong and insistent even though largely silenced in outward expression by the public opinion of the nation. Some of this opposition is, of course, mere envy; the disappointment of displaced demagogues and the spite of narrow minds. But aside from this, there is among educated and thoughtful colored men in all parts of the land a feeling of deep regret, sorrow, and apprehension at the wide currency and ascendancy which some of Mr. Washington’s theories have gained. …

Mr. Washington represents in Negro thought the old attitude of adjustment and submission; but adjustment at such a peculiar time as to make his programme unique. This is an age of unusual economic development, and Mr. Washington’s programme naturally takes an economic cast, becoming a gospel of Work and Money to such an extent as apparently almost completely to overshadow the higher aims of life. Moreover, this is an age when the more advanced races are coming in closer contact with the less developed races, and the race-feeling is therefore intensified; and Mr. Washington’s programme practically accepts the alleged inferiority of the Negro races. Again, in our own land, the reaction from the sentiment of war time has given impetus to race-prejudice against Negroes, and Mr. Washington withdraws many of the high demands of Negroes as men and American citizens. In other periods of intensified prejudice all the Negro’s tendency to self-assertion has been called forth; at this period a policy of submission is advocated. In the history of nearly all other races and peoples the doctrine preached at such crises has been that manly self-respect is worth more than lands and houses, and that a people who voluntarily surrender such respect, or cease striving for it, are not worth civilizing.

In answer to this, it has been claimed that the Negro can survive only through submission. Mr. Washington distinctly asks that black people give up, at least for the present, three things,—

First, political power,

Second, insistence on civil rights,

Third, higher education of Negro youth,

and concentrate all their energies on industrial education, the accumulation of wealth, and the conciliation of the South. This policy has been courageously and insistently advocated for over fifteen years, and has been triumphant for perhaps ten years. As a result of this tender of the palm-branch, what has been the return? In these years there have occurred:

The disfranchisement of the Negro.

The legal creation of a distinct status of civil inferiority for the Negro.

The steady withdrawal of aid from institutions for the higher training of the Negro.

These movements are not, to be sure, direct results of Mr. Washington’s teachings; but his propaganda has, without a shadow of doubt, helped their speedier accomplishment. The question then comes: Is it possible, and probable, that nine millions of men can make effective progress in economic lines if they are deprived of political rights, made a servile caste, and allowed only the most meagre chance for developing their exceptional men? If history and reason give any distinct answer to these questions, it is an emphatic No. …

The other class of Negroes who cannot agree with Mr. Washington has hitherto said little aloud. They deprecate the sight of scattered counsels, of internal disagreement; and especially they dislike making their just criticism of a useful and earnest man an excuse for a general discharge of venom from small-minded opponents. Nevertheless, the questions involved are so fundamental and serious that it is difficult to see how men like the Grimkes, Kelly Miller, J.W.E. Bowen, and other representatives of this group, can much longer be silent. Such men feel in conscience bound to ask of this nation three things.

The right to vote.

Civic equality.

The education of youth according to ability. …

Source: http://historymatters.gmu.edu/d/40/

5. A Report of the Homestead Strike of 1892

“‘The Incident’ of the 6th of July,” Illustrated American, July 16, 1892.

NOTHING more dramatic in the History of Labor and Capital is recorded than the Incident of the 6th of July.

The forces of the Nineteenth Century are Capital and Labor, united they transform the desert into a garden, in collision they convert the garden into a waste.

On the 6th of July, 1892, at Homestead, Penn., the Forces met. The sound of the shock echoed through the labor markets of the world.

In this age we regard the French Revolution with surprise, we wonder at the growth of the power of the mob, we are amazed at the brutality of the people, and we are astonished at the spectacle afforded by the savagery of women.

The Incident of the 6th of July affords a parallel in diminutive form, and is pregnant with meaning.

Let us see !

A certain man, who has risen from the ranks of labor by thrift, cleverness, and lucky transactions, has amassed riches. His name is Andrew Carnegie; his fortune is written in the millions. Much of this fortune is invested in steel rolling mills at Homestead. These works cover one hundred and fifty acres of ground; here work four thousand five hundred men. The smoke of the flumes ascend day and night to the god of commerce, and the high price of bread consumes the day wage of the toilers.

Four years ago Carnegie gave $500,000 to the campaign fund which promised him “protection” or monopoly. Fourteen competing rolling mills have passed away and one hundred acres have been added to the Carnegie plant.

A few weeks since Carnegie’s partners decided that men seeking the protection of a union or brotherhood should not be employed at the works. He who sought “protection” denied protection,

As the custom is, the time came when the Employer and Employe should fix the price of wages. The Man asked one dollar more than the Master was willing to pay. “Protection” had poured gold into his strong box, and raised the price of beef, bread, and clothing.

The Wage-giver and the Wage-taker could not agree about the one dollar.

And the works shut down!

The Advisory Committee of the locked-out workmen said: Let there be order! And there was order.

The Master of the mill said: Let there be protection! A fence, twelve feet high, of stout boards mounted on three feet of slag, four miles in length, closed in the works. This fence was bored with holes to allow the passage of a rifle barrel from the inside. It was surmounted with barbed wires, connected with powerful dynamos, so that they could be made alive with electricity. Search lights were mounted at certain points, and nozzles connected with hydrants supplied with boiling water at others. At an excellent point of vantage, a detective camera was set up in order to secure photographs of invaders, for the purpose of prosecution in the courts of law controlled by the Master of the Mill.

So much for the stockade. The Hessians were to be imported. The Master of the Mill said: Hire Pinkerton’s men.

A foreign armed force was to settle the question of one dollar in wages.

“We have done our best to preserve order and have succeeded in preserving it. We cannot now, of course, be responsible for anything that may occur in consequence of your action.” So said the Advisory Committee to the Sheriff.

It is the morning of July 6. The sun has not risen, the morning star shines in the inverted blue bowl over the silent factory and on the river.

Men watch the coming of the armed deputies—the paid assassins of the Master of the Mill.

It is half-past two in the morning. A scout stationed at Lock No. 1, on the Monongahela River, reports the arrival of two barges in charge of a river steamer. They contain armed men.

Now up—filling the great star-bespeckled bowl—goes the long, sad wail of the steam whistle at the electric light plant.

It is the voice of Labor shrieking to the wage-worker to rise and make haste, for armed Capital is to take possession of the workshop. Flash lights start from many points. The night is over; horsemen dash through the streets of Homestead yelling: " To the river; to the river—the Pinkertons are coming!"

They go to the river.

Half-dressed men and women, boys, girls, and children rush to the river. Each has a weapon—some of guns, revolvers, knives, heavy irons, and sound sticks. Labor is in arms.

The river steamer Little Bill crowds on steam and speeds to the landing; the mob on the bank races to intercept the armed men. It is a mad race in the morning light. Down come fences and other impediments. When the barges are within one hundred feet of the landing, the advance guard of the mob is on the ground to contest the holding of it.

The mob warned off the armed men: “Don’t land or we’ll brain you.”

Out from the barge came the plank. Every Pinkerton man levelled his Winchester rifle. A few of the bravest of them endeavored to land.

The sight of this infuriated the mob. They rushed forward and attempted to seize the rifles.

One Hugh O’Donnell, a man of character and heroic soul, a mill hand, with three others, hatless and coatless, with their backs to the Pinkertons, in fearful peril of their lives, besought the mob to fall back: “In God’s name,” he cried, “my good fellows, keep back; don’t press down and force them to do murder!”

A sharp report of a Winchester rifle from the bow of the boat answered him. In an instant there was a sheet of flame —a rain of leaden hail. The crowd fell back a few feet, then advanced, pouring deadly shots into the invading force.

The boat pulled out into the stream.

There were dead men on both sides.

And so ended the first battle of the morning.

When the armed hirelings of Andrew Carnegie poured their deadly volley in the ranks of the men who dared to demand one dollar more on their wages, there were few guns among the people. At the crack of the Pinkertons first rifle men rushed to their homes for firearms and prepared for battle in earnest. At half-past six a second attempt at landing was repulsed.

Out on the stream lay the barges. The hot sun beat down upon them and the heat was suffocating. Pinkerton’s men needed air. Rats require that. They started to cut air holes, but the bullets of the mob on shore were too much for them. They decided that hot air was better than bullets.

An attempt was made to fire the barges by pouring burning oil on the river, but fortunately this terrible ordeal was spared the Pinkertons. …

The spokesman of the Pinkertons announced that they would surrender if assured of protection from the mob.

They landed. Their arms were taken from them. With heads uncovered, to distinguish them from the mill hands, they passed along between two rows of guards armed with Winchesters. There were two hundred and fifty Pinkertons in line. And so those who came to hold the Carnegie mills were led trembling away to the lock-up.

Silently, sadly, and filled with fear, the disarmed Pinkertons, some bleeding, with bedraggled clothing, haggard and pale-faced, walked between their captors. Some held small bags with clothing. Alongside crowded the surging mass of hard-fisted men hurling epithets at them. For some time they walked thus, hoping for the shelter of the jail.

Now woman comes to the front!

One snatched a bag, tore from it a white shirt and waved it. This action was almost a signal to the brigade of women. They seized every bag and scattered the contents. With yells and shouts the crowd cheered the women. There was a fine humor here; to scatter the clothing of those who had come to scatter them.

Another woman threw sand into the eyes of a Pinkerton and cut him with a stone. Then, in spite of the guards, the women cast stones and missiles at the unprotected Pinkertons. The guards hurried them over the unlevel ground to the jail.

There they were a sorry lot. Cut, bruised, with eyes knocked out, with noses smashed, the invading, conquered army escaped death in the jail. So ended an expedition of two hundred and eighty men, armed with Winchesters, and supplied with provisions for three months.

And behind the high board fence, with the barbed wires charged with electricity, rest the mill hands waiting the developments of the future.

Source: http://ehistory.osu.edu/osu/mmh/HomesteadStrike1892/HistoryofSevenDays/incident.cfm

6. Text of the Geary Act of 1892

Fifty-Second Congress. Session I. 1892.

Chapter 60.—An act to prohibit the coming of Chinese persons into the United States.

Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, That all laws now in force prohibiting and regulating the coming into this country of Chinese persons and persons of Chinese descent are hereby continued in force for a period of ten years from the passage of this act.

SEC. 2. That any Chinese person or person of Chinese descent, when convicted and adjudged under any of said laws to be not lawfully entitled to be or remain in the United States, shall be removed from the United States to China, unless he or they shall make it appear to the justice, judge, or commissioner before whom he or they are tried that he or they are subjects or citizens of some other country, in which case he or they shall be removed from the United States to such country: Provided, That in any case where such other country of which such Chinese person shall claim to be a citizen or subject shall demand any tax as a condition of removal of such person to that country, he or she shall be removed to China.

SEC. 3. That any Chinese person or person of Chinese descent arrested under the provisions of this act or the acts hereby extended shall be adjudged to be unlawfully within the United States unless such person shall establish, by affirmative proof, to the satisfaction of such justice, judge, or commissioner, his lawful right to remain in the United States.

SEC. 4. That any Chinese person or person of Chinese descent convicted and adjudged to be not lawfully entitled to be or remain in the United States shall be imprisoned at hard labor for a period of not exceeding on e year and thereafter removed from the United States, as hereinbefore provided.

SEC. 5. That after the passage of this act on an application to any judge or court of the United States in the first instance for a writ of habeas corpus, by a Chinese person seeking to land in the United States, to whom that privilege has been denied, no bail shall be allowed, and such application shall be heard and determined promptly without unnecessary delay.

SEC. 6. And it shall be the duty of all Chinese laborers within the limits of the United States, at the time of the passage of this act, and who are entitled to remain in the United States, to apply to the collector of internal revenue of their respective districts, within no year after the passage of this act, for a certificate of residence, and any Chinese laborer, within the limits of the United States, who shall neglect, fail, or refuse to comply with the provisions of this act, or who, after one year from the passage hereof, shall be found within the jurisdiction of the United States without such certificate of residence, shall be deemed and adjudged to be unlawfully within the United States, and may be arrested, by any United States customs official, collector of internal revenue or his deputies, United States marshal or his deputies, and taken before a United States judge, whose duty it shall be to order that he be deported from the United States as hereinbefore provided, unless he shall establish clearly to the satisfaction of said judge, that by reason of accident, sickness or other unavoidable cause, he has been unable to procure his certificate, and to the satisfaction of the court, and by at least one credible white witness, that he was a resident of the United States at the time of the passage of this act; and if upon the hearing, it shall appear that he is so entitled to a certificate, it shall be granted upon his paying the cost. Should it appear that said Chinaman had procured a certificate which has been lost or destroyed, he shall be detained and judgment suspended a reasonable time to enable him to procure a duplicate from the officer granting it, and in such cases, the cost of said arrest and trial shall be in the discretion of the court. And any Chinese person other than a Chinese laborer, having a right to be and remain in the United States, desiring such certificate as evidence of such right may apply for and receive the same without charge.

SEC. 7. That immediately after the passage of this act, the Secretary of the Treasury shall make such rules and regulations as may be necessary for the efficient execution of this act, and shall prescribe the necessary forms and furnish the necessary blanks to enable collectors of internal revenue to issue the certificates required hereby, and make such provisions that certificates may be procured in localities convenient to the applicant, and shall contain the name, age, local residence and occupation of the applicants, such other description of the applicant as shall be prescribed by the Secretary of the Treasury, and a duplicate thereof shall be filed in the office of the collector of internal revenue for the district within which such Chinaman makes application.

SEC. 8. That any person who shall knowingly and falsely alter or substitute any name for the name written in such certificate or forge such certificate, or knowing utter any forged or fraudulent certificate, or falsely personate any person name in such certificate, shall be guilty of a misdemeanor, and upon conviction thereof shall be fined in a sum not exceeding one thousand dollars or imprisoned in the penitentiary for a term of not more than five years.

SEC. 9. The Secretary of the Treasury may authorize the payment of such compensation in the nature of fees to the collectors of internal revenue, for services performed under the provisions of this act in addition to salaries now allowed by law, as he shall deem necessary, not exceeding the sum of one dollar for each certificate issued.

Approved, May 5, 1892.

Source: San Francisco Chinatown

7. Instructions for the Celebration of Columbus Day (1892)

A page from The Youth’s Companion, September 8, 1892