Readings for April 10

- Media

- Readings

- 1. Declaration of Sentiments of the Seneca Falls Convention (1848)

- 2. A National Convention of Free Black Leaders Addresses “the Colored People” (1848)

- 3. Abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison Burns the Constitution (1854)

- 4. Abraham Lincoln Speaks at Peoria, Illinois (1854)

- 5. Abraham Lincoln Debates Stephen Douglas (1858)

- Articles on Race from Scientific American

Media

1. Daguerreotypes of Cincinnati in 1848

Conservators recently restored some damaged panoramic photographs of the Cincinnati waterfront taken in 1848. Take a look at the article about the photos and spend some time panning around the picture.

2. Silent Film of Scenes from Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1903)

Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin, published in 1852, was one of the best-selling novels of the nineteenth century. It also became a mass culture phenomenon, spawning card games, children’s books, song and stage adaptations, and even anti-Tom novels.

Don’t try to read everything at those links—though glancing at them will give you the flavor of the novel’s long-lasting reach. But do watch this clip from a 1903 silent film made by Thomas Edison and Edwin Porter.

3. “Slave Market of America” Broadside (1836)

Take a close-up look at this abolitionist broadside protesting the existence of slave markets in Washington, D.C. To read the text, you’ll probably need to click on the hi-resolution TIFF file, but beware: it’s a huge file so you’ll have the most luck looking at this on the campus network, and preferably with an Ethernet connection.

Readings

1. Declaration of Sentiments of the Seneca Falls Convention (1848)

Woman’s Rights Convention, Held at Seneca Falls, 19-20 July 1848

On the morning of the 19th, the Convention assembled at 11 o’clock. . . . The Declaration of Sentiments, offered for the acceptance of the Convention, was then read by E. C. Stanton. A proposition was made to have it re-read by paragraph, and after much consideration, some changes were suggested and adopted. The propriety of obtaining the signatures of men to the Declaration was discussed in an animated manner: a vote in favor was given; but concluding that the final decision would be the legitimate business of the next day, it was referred.

[In the afternoon] The reading of the Declaration was called for, an addition having been inserted since the morning session. A vote taken upon the amendment was carried, and papers circulated to obtain signatures. The following resolutions were then read:

Whereas, the great precept of nature is conceded to be, “that man shall pursue his own true and substantial happiness,” Blackstone, in his Commentaries, remarks, that this law of Nature being coeval with mankind, and dictated by God himself, is of course superior in obligation to any other. It is binding over all the globe, in all countries, and at all times; no human laws are of any validity if contrary to this, and such of them as are valid, derive all their force, and all their validity, and all their authority, mediately and immediately, from this original; Therefore,

Resolved, That such laws as conflict, in any way, with the true and substantial happiness of woman, are contrary to the great precept of nature, and of no validity; for this is “superior in obligation to any other.

Resolved, That all laws which prevent woman from occupying such a station in society as her conscience shall dictate, or which place her in a position inferior to that of man, are contrary to the great precept of nature, and therefore of no force or authority.

Resolved, That woman is man’s equal—was intended to be so by the Creator, and the highest good of the race demands that she should be recognized as such.

Resolved, That the women of this country ought to be enlightened in regard to the laws under which they -live, that they may no longer publish their degradation, by declaring themselves satisfied with their present position, nor their ignorance, by asserting that they have all the rights they want.

Resolved, That inasmuch as man, while claiming for himself intellectual superiority, does accord to woman moral superiority, it is pre-eminently his duty to encourage her to speak, and teach, as she has an opportunity, in all religious assemblies.

Resolved, That the same amount of virtue, delicacy, and refinement of behavior, that is required of woman in the social state, should also be required of man, and the same tranegressions should be visited with equal severity on both man and woman.

Resolved, That the objection of indelicacy and impropriety, which is so often brought against woman when she addresses a public audience, comes with a very ill grace from those who encourage, by their attendance, her appearance on the stage, in the concert, or in the feats of the circus.

Resolved, That woman has too long rested satisfied in the circumscribed limits which corrupt customs and a perverted application of the Scriptures have marked out for her, and that it is time she should move in the enlarged sphere which her great Creator has assigned her.

Resolved, That it is the duty of the women of this country to secure to themselves their sacred right to the elective franchise.

Resolved, That the equality of human rights results necessarily from the fact of the identity of the race in capabilities and responsibilities.

Resolved, therefore, That, being invested by the Creator with the same capabilities, and the same consciousness of responsibility for their exercise, it is demonstrably the right and duty of woman, equally with man, to promote every righteous cause, by every righteous means; and especially in regard to the great subjects of morals and religion, it is self-evidently her right to participate with her brother in teaching them, both in private and in public, by writing and by speaking, by any instrumentalities proper to be used, and in any assemblies proper to be held; and this being a self-evident truth, growing out of the divinely implanted principles of human nature, any custom or authority adverse to it, whether modern or wearing the hoary sanction of antiquity, is to be regarded as self-evident falsehood, and at war with the interests of mankind.

Thursday Morning.

The Convention assembled at the hour appointed, James Mott, of Philadelphia, in the Chair. The minutes of the previous day having been read, E. C. Stanton again read the Declaration of Sentiments, which was freely discussed . . . and was unanimously adopted, as follows:

Declaration of Sentiments.

When, in the course of human events, it becomes necessary for one portion of the family of man to assume among the people of the earth a position different from that which they have hitherto occupied, but one to which the laws of nature and of nature’s God entitle them, a decent respect to the opinions of mankind requires that they should declare the causes that impel them to such a course.

We hold these truths to be self-evident: that all men and women are created equal; that they are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights; that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness; that to secure these rights governments are instituted, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed. Whenever any form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the right of those who suffer from it to refuse allegiance to it, and to insist upon the institution of a new government, laying its foundation on such principles, and organizing its powers in such form as to them shall seem most likely to effect their safety and happiness. Prudence, indeed, will dictate that governments long established should not be changed for light and transient causes; and accordingly, all experience hath shown that mankind are more disposed to suffer, while evils are sufferable, than to right themselves by abolishing the forms to which they are accustomed. But when a long train of abuses and usurpations, pursuing invariably the same object, evinces a design to reduce them under absolute despotism, it is their duty to throw off such government, and to provide new guards for their future security. Such has been the patient sufferance of the women under this government, and such is now the necessity which constrains them to demand the equal station to which they are entitled.

The history of mankind is a history of repeated injuries and usurpations on the part of man toward woman, having in direct object the establishment of an absolute tyranny over her. To prove this, let facts be submitted to a candid world.

He has never permitted her to exercise her inalienable right to the elective franchise.

He has compelled her to submit to laws, in the formation of which she had no voice.

He has withheld from her rights which are given to the most ignorant and degraded men—both natives and foreigners.

Having deprived her of this first right of a citizen, the elective franchise, thereby leaving her without representation in the halls of legislation, he has oppressed her on all sides.

He has made her, if married, in the eye of the law, civilly dead.

He has taken from her all right in property, even to the wages she earns.

He has made her, morally, an irresponsible being, as she can commit many crimes with impunity, provided they be done in the presence of her husband. In the covenant of marriage, she is compelled to promise obedience to her husband, he becoming, to all intents and purposes, her master—the law giving him power to deprive her of her liberty, and to administer chastisement.

He has so framed the laws of divorce, as to what shall be the proper causes of divorce; in case of separation, to whom the guardianship of the children shall be given; as to be wholly regardless of the happiness of women—the law, in all cases, going upon the false supposition of the supremacy of man, and giving all power into his hands.

After depriving her of all rights as a married woman, if single and the owner of property, he has taxed her to support a government which recognizes her only when her property can be made profitable to it.

He has monopolized nearly all the profitable employments, and from those she is permitted to follow, she receives but a scanty remuneration.

He closes against her all the avenues to wealth and distinction, which he considers most honorable to himself. As a teacher of theology, medicine, or law, she is not known.

He has denied her the facilities for obtaining a thorough education—all colleges being closed against her.

He allows her in Church as well as State, but a subordinate position, claiming Apostolic authority for her exclusion from the ministry, and, with some exceptions, from any public participation in the affairs of the Church.

He has created a false public sentiment, by giving to the world a different code of morals for men and women, by which moral delinquencies which exclude women from society, are not only tolerated but deemed of little account in man.

He has usurped the prerogative of Jehovah himself, claiming it as his right to assign for her a sphere of action, when that belongs to her conscience and her God.

He has endeavored, in every way that he could to destroy her confidence in her own powers, to lessen her self-respect, and to make her willing to lead a dependent and abject life.

Now, in view of this entire disfranchisement of one-half the people of this country, their social and religious degradation,—in view of the unjust laws above mentioned, and because women do feel themselves aggrieved, oppressed, and fraudulently deprived of their most sacred rights, we insist that they have immediate admission to all the rights and privileges which belong to them as citizens of these United States.

In entering upon the great work before us, we anticipate no small amount of misconception, misrepresentation, and ridicule; but we shall use every instrumentality within our power to effect our object. We shall employ agents, circulate tracts, petition the State and national Legislatures, and endeavor to enlist the pulpit and the press in our behalf.We hope this Convention will be followed by a series of Conventions, embracing every part of the country.

Firmly relying upon the final triumph of the Right and the True, we do this day affix our signatures to this declaration.

At the appointed hour the meeting convened. The minutes having been read, the resolutions of the day before were read and taken up separately. Some, from their self-evident truth, elicited but little remark; others, after some criticism, much debate, and some slight alterations, were finally passed by a large majority.

[At an evening session] Lucretia Mott offered and spoke to the following resolution:

Resolved, That the speedy success of our cause depends upon the zealous and untiring efforts of both men and women, for the overthrow of the monopoly of the pulpit, and for the securing to woman an equal participation with men in the various trades, professions and commerce.

The Resolution was adopted.

Source: Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony Papers Project

2. A National Convention of Free Black Leaders Addresses “the Colored People” (1848)

Published in Frederick Douglass’s newspaper, The North Star, on September 29, 1848.

Fellow Countrymen:

Under a solemn sense of duty, inspired by our relation to you as fellow sufferers under the multiplied and grievous wrongs to which we as a people are universally subjected,–we, a portion of your brethren, assembled in National Convention, at Cleveland, Ohio, take the liberty to address you on the subject of our mutual improvement and social elevation.

The condition of our variety of the human family, has long been cheerless, if not hopeless, in this country. The doctrine perseveringly proclaimed in high places in church and state, that it is impossible for colored men to rise from ignorance and debasement, to intelligence and respectability in this country, has made a deep impression upon the public mind generally, and is not without its effect upon us. Under this gloomy doctrine, many of us have sunk under the pall of despondency, and are making no effort to relieve ourselves, and have no heart to assist others. It is from this despond that we would deliver you. It is from this slumber we would rouse you. The present, is a period of activity and hope. The heavens above us are bright, and much of the darkness that overshadowed us has passed away. We can deal in the language of brilliant encouragement, and speak of success with certainty. That our condition has been gradually improving, is evident to all, and that we shall yet stand on a common platform with our fellow countrymen, in respect to political and social rights, is certain. The spirit of the age — the voice of inspiration — the deep longings of the human soul — the conflict of right with wrong–the up-ward tendency of the oppressed throughout the world, abound with evidence complete and ample, of the final triumph of right over wrong, of freedom over slavery, and equality over caste. To doubt this, is to forget the past, and blind our eyes to the present, as well as to deny and oppose the great law of progress, written out by the hand of God on the human soul.

Great changes for the better have taken place and are still taking place. The last ten years have witnessed a mighty change in the estimate in which we as a people are regarded, both in this and other lands. England has given liberty to nearly one million, and France has emancipated three hundred thousand of our brethren, and our own country shakes with the agitation of our rights. Ten or twelve years ago, an educated colored man was regarded as a curiosity, and the thought of a colored man as an author, editor, lawyer or doctor, had scarce been conceived. Such, thank Heaven, is no longer the case. There are now those among us, whom we are not ashamed to regard as gentlemen and scholars, and who are acknowledged to be such, by many of the most learned and respectable in our land. Mountains of prejudice have been removed, and truth and light are dispelling the error and darkness of ages. The time was, when we trembled in the presence of a white man, and dared not assert, or even ask for our rights, but would be guided, directed, and governed, in any way we were demanded, without ever stopping to enquire whether we were right or wrong. We were not only slaves, but our ignorance made us willing slaves. Many of us uttered complaints against the faithful abolitionists, for the broad assertion of our rights; thought they went too far, and were only making our condition worse. This sentiment has nearly ceased to reign in the dark abodes of our hearts; we begin to see our wrongs as clearly, and comprehend our rights as fully, and as well as our white countrymen. This is a sign of progress; and evidence which cannot be gainsayed. It would be easy to present in this connection, a glowing comparison of our past with our present condition, showing that while the former was dark and dreary, the present is full of light and hope. It would be easy to draw a picture of our present achievements, and erect upon it a glorious future.

But, fellow countrymen, it is not so much our purpose to cheer you by the progress we have already made, as it is to stimulate you to still higher attainments. We have done much, but there is much more to be done. — While we have undoubtedly great cause to thank God, and take courage for the hopeful changes which have taken place in our condition, we are not without cause to mourn over the sad condition which we yet occupy. We are yet the most oppressed people in the world. In the Southern states of this Union, we are held as slaves. All over that wide region our paths are marked with blood. Our backs are yet scarred by the lash, and our souls are yet dark under the pall of slavery. — Our sisters are sold for purposes of pollution, and our brethren are sold in the market, with beasts of burden. Shut up in the prison-house of bondage — denied all rights, and deprived of all privileges, we are blotted from the page of human existence, and placed beyond the limits of human regard. Death, moral death, has palsied our souls in that quarter, and we are a murdered people.

In the Northern states, we are not slaves to individuals, not personal slaves, yet in many respects we are the slaves of the community. We are, however, far enough removed from the actual condition of the slave, to make us largely responsible for their continued enslavement, or their speedy deliverance from chains. For in the proportion which we shall rise in the scale of human improvement, in that proportion do we augment the probabilities of a speedy emancipation of our enslaved fellow-countrymen. It is more than a mere figure of speech to say, that we are as a people, chained together. We are one people — one in general complexion, one in a common degradation, one in popular estimation. As one rises, all must rise, and as one falls all must fall. Having now, our feet on the rock of freedom, we must drag our brethren from the slimy depths of slavery, ignorance, and ruin. Every one of us should be ashamed to consider himself free, while his brother is a slave. — The wrongs of our brethren, should be our constant theme. There should be no time too precious, no calling too holy, no place too sacred, to make room for this cause. We should not only feel it to be the cause of humanity, but the cause of christianity, and fit work for men and angels. We ask you to devote yourselves to this cause, as one of the first, and most successful means of self improvement. In the careful study of it, you will learn your own rights, and comprehend your own responsibilities, and, scan through the vista of coming time, your high, and God-appointed destiny. Many of the brightest and best of our number, have become such by their devotion to this cause, and the society of white abolitionists. The latter have been willing to make themselves of no reputation for our sake, and in return, let us show ourselves worthy of their zeal and devotion. Attend anti-slavery meetings, show that you are interested in the subject, that you hate slavery, and love those who are laboring for its overthrow.–Act with white Abolition societies wherever you can, and where you cannot, get up societies among yourselves, but without exclusiveness. It will be a long time before we gain all our rights; and although it may seem to conflict with our views of human brotherhood, we shall undoubtedly for many years be compelled to have institutions of a complexional character, in order to attain this very idea of human brotherhood. We would, however, advise our brethren to occupy memberships and stations among white persons, and in white institutions, just so fast as our rights are secured to us.

Never refuse to act with a white society or institution because it is white, or a black one, because it is black. But act with all men without distinction of color. By so acting, we shall find many opportunities for removing prejudices and establishing the rights of all men. We say avail yourselves of white institutions, not because they are white, but because they afford a more convenient means of improvement. But we pass from these suggestions, to others which may be deemed more important. In the Convention that now addresses you, there has been much said on the subject of labor, and especially those departments of it, with which we as a class have been long identified. You will see by the resolutions there adopted on that subject, that the Convention regarded those employments though right in themselves, as being nevertheless, degrading to us as a class, and therefore, counsel you to abandon them as speedily as possible, and to seek what are called the more respectable employments. While the Convention do not inculcate the doctrine that any kind of needful toil is in itself dishonorable, or that colored persons are to be exempt from what are called menial employments, they do mean to say that such employments have been so long and universally filled by colored men, as to become a badge of degradation, in that it has established the conviction that colored men are only fit for such employments. We therefore, advise you by all means, to cease from such employments, as far as practicable, by pressing into others. Try to get your sons into mechanical trades; press them into the blacksmith’s shop, the machine shop, the joiner’s shop, the wheelwright’s shop, the cooper’s shop, and the tailor’s shop.

Every blow of the sledge hammer, wielded by a sable arm, is a powerful blow in support of our cause. Every colored mechanic, is by virtue of circumstances, an elevator of his race. Every house built by black men, is a strong tower against the allied hosts of prejudice. It is impossible for us to attach too much importance to this aspect of the subject. Trades are important. Wherever a man may be thrown by misfortune, if he has in his hands a useful trade, he is useful to his fellow man, and will be esteemed accordingly; and of all men in the world who need trades we are the most needy.

Understand this, that independence is an essential condition of respectability. To be dependent, is to be degraded. Men may indeed pity us, but they cannot respect us. We do not mean that we can become entirely independent of all men; that would be absurd and impossible, in the social state. But we mean that we must become equally independent with other members of the community. That other members of the community shall be as dependent upon us, as we upon them. — That such is not now the case, is too plain to need an argument. The houses we live in are built by white men — the clothes we wear are made by white tailors — the hats on our heads are made by white hatters, and the shoes on our feet are made by white shoe-makers, and the food that we eat, is raised and cultivated by white men. Now it is impossible that we should ever be respected as a people, while we are so universally and completely dependent upon white men for the necessaries of life. We must make white persons as dependent upon us, as we are upon them. This cannot be done while we are found only in two or three kinds of employments, and those employments have their foundation chiefly, if not entirely, in the pride and indolence of the white people. Sterner necessities, will bring higher respect.

The fact is, we must not merely make the white man dependent upon us to shave him but to feed him; not merely dependent upon us to black his boots, but to make them. A man is only in a small degree dependent on us when he only needs his boots blacked, or his carpet bag carried; as a little less pride, and a little more industry on his part, may enable him to dispense with our services entirely. As wise men it becomes us to look forward to a state of things, which appears inevitable. The time will come, when those menial employments will afford less means of living than they now do. What shall a large class of our fellow countrymen do, when white men find it economical to black their own boots, and shave themselves. What will they do when white men learn to wait on themselves? We warn you brethren, to seek other and more enduring vocations.

Let us entreat you to turn your attention to agriculture. Go to farming. Be tillers of the soil. On this point we could say much, but the time and space will not permit. Our cities are overrun with menial laborers, while the country is eloquently pleading for the hand of industry to till her soil, and reap the reward of honest labor. We beg and intreat you, to save your money — live economically — dispense with finery, and the gaities which have rendered us proverbial, and save your money. Not for the senseless purpose of being better off than your neighbor, but that you may be able to educate your children, and render your share to the common stock of prosperity and happiness around you. It is plain that the equality which we aim to accomplish, can only be achieved by us, when we can do for others, just what others can do for us. We should therefore, press into all the trades, professions and callings, into which honorable white men press.

We would in this connection, direct your attention to the means by which we have been oppressed and degraded. Chief among those means, we may mention the press. This engine has brought to the aid of prejudice, a thousand stings. Wit, ridicule, false philosophy, and an impure theology, with a flood of low black-guardism, come through this channel into the public mind; constantly feeding and keeping alive against us, the bitterest hate. The pulpit too, has been arrayed against us. Men with sanctimonious face, have talked of our being descendants of Ham — that we are under a curse, and to try to improve our condition, is virtually to counteract the purposes of God!

It is easy to see that the means which have been used to destroy us, must be used to save us. The press must be used in our behalf: aye! we must use it ourselves; we must take and read newspapers; we must read books, improve our minds, and put to silence and to shame, our opposers.

Dear Brethren, we have extended these remarks beyond the length which we had allotted ourselves, and must now close, though we have but hinted at the subject. Trusting that our words may fall like good seed upon the good ground; and hoping that we may all be found in the path of improvement and progress,

We are your friends and servants,

(Signed by the Committe, in behalf of the Convention

Frederick Dougless,

H. Bibb,

W.L. Day,

D.H. Jenkins,

A.H. Francis.

Source: Teaching American History

3. Abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison Burns the Constitution (1854)

From the Liberator (Boston), July 7, 1854

THE MEETING AT FRAMINGHAM

On the Fourth of July, (Tuesday last,) was of almost unprecedented numbers, and great unanimity and enthusiasm. The only drawback on the entire enjoyment of the day arose from the heat of the weather, which was extreme. …

Mr. Garrison read appropriate passages of Scripture, and an anti-slavery hymn was sung by the whole assembly. …

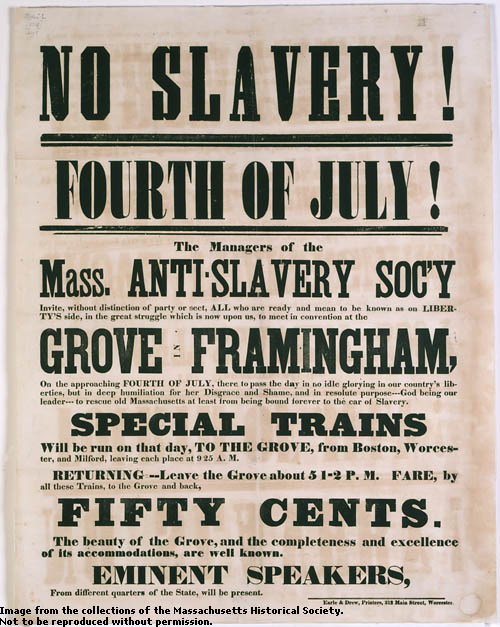

Broadside poster for the abolitionist meeting at Framingham

The President of the day (Mr. Garrison) then addressed the vast assembly as follows:–

FRIENDS OF FREEDOM AND HUMANITY: …

To-day, we are called to celebrate the seventy-eighth anniversary of American Independence. In what spirit? with what purpose? to what end? Confining our attention exclusively to the fact, that, on the 4th of July, 1776, it was boldly declared to the world by our revolutionary sires, as ‘self-evident truths, that all men are created equal—that they are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights—that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness’—we have abundant reason for exultation, gratitude, thanksgiving. This was the greatest political event in the annals of time. … It was not a declaration of equality of property, bodily strength or beauty, intellectual or moral development, industrial or inventive powers, but equality of RIGHTS—not of one race, but of all races. In it was included every human being—the most benighted as well as the most enlightened, the most degraded as well as the most elevated, the most helpless as well as the most powerful. …

But where can our Declaration be proclaimed, and faithfully applied to men and governments, without subjecting the enforcer of it to ridicule, odium, persecution, imprisonment, martyrdom, or lynch law? Begin at home. How many really believe in its truthfulness and rationality here at the North? How many are prepared to denounce the hideous crime of slaveholding as a sin against God? How many are avowed abolitionists? And what is an abolitionist but a sincere believer in the Declaration of ’76? How many are at a loss to discover reasons, and frame excuses, and multiply defences, for the conduct of the slaveholders against its impeachment by the friends of the slave? What has been the history of the anti-slavery struggle at the North for the last twenty-five years, but a history of the personal defamation and ostracism of its advocates, religiously, politically, socially? Have they not been ranked amongst the vilest of the vile, the most dangerous members of the community, heretics and infidels of the most malignant type, filled with the spirit of sedition and all unrighteousness? … All this at the North, even to this day.

At the South, who can safely avow his belief in the inalienable rights of man, irrespective of complexional caste? What man dare openly tell the slave that he has a God-given right to his freedom at any moment? What of the Southern church? ‘A cage of unclean birds and the synagogue of Satan.’ What of the Southern clergy? Vindicating slavery as a divine institution, and branding abolitionism as of the devil. What of the Southern press? Infernal in its spirit and language toward all such as avow their hostility to slavery, and eager to hand them over to the tender mercies of the mob.

The result is, that, whether at the North or the South, a straight-foward, manly, inflexible adherence to the Declaration of Independence is attended with great personal discomfort, loss of social position, political proscription, and religious excommunication; to which is superadded at the South, the infliction of lynch law, either by compelling the friend of impartial liberty to seek safety in flight, or subjecting him to a coat of tar and feathers, or thrusting him into prison, or hanging him summarily by the neck, or shooting him with a revolver. …

Since the war of the Revolution was declared, we have grown in population from three millions to twenty-five millions. This is an unparalleled growth. But a Republic is not made by a teeming population, else Russia and China might claim to be Republics. Our territorial lines reach from the Atlantic to the Pacific. But extent of territory is not the true criterion of national attainment. The land is filled with material prosperity: we are better fed, better clad, better sheltered, than any other people. But great riches and general prosperity may exist with little virtue and small love of liberty. … We are proud of our ships, our commerce, our manufactures, and talk of ‘our manifest destiny’ to annex, conquer or crush whatever stands in our way to universal empire. But to this nation, the language of the prophet is strictly and fearfully applicable:—’The pride of thine heart hath deceived thee, thou whose habitation is high; that saith in thine heart, Who shall bring me down to the ground? Though thou exalt thyself as the eagle, and though thou set thy nest among the stars, thence will I bring thee down, saith the Lord. …

Alas, our greed is insatiable, our rapacity boundless, our disregard of justice profligate to the last degree. We have degenerated in regard to our reverence for the higher law of God, for what is morally obligatory, for the cause of liberty. … The forms of a republic are yet left to us, but corruption is general, and mal-administration the order of the day. … The condition required of every man holding office under the government is a ready acquiescence in whatever the Slave Power may dictate. … On the floor of the American Senate, the Declaration of Independence has been scouted as a tissue of lies and absurdities!!! A proposition has also been presented to that body, to recall from the African coast our naval force, located there to suppress the piratical slave traffic, and as preliminary to the opening of that traffic as a part of the legitimate commerce of the United States! The boldest and most astounding plans are openly avowed for the unlimited annexation of foreign territory for slaveholding purposes. …

Such is our condition, such are our prospects, as a people, on the 4th of July, 1854!

Mr. Garrison said that he should now proceed to perform an action which would be the testimony of his own soul to all present, of the estimation in which he held the pro-slavery laws and deeds of the nation. Producing a copy of the Fugitive Slave Law, he set fire to it, and it burnt to ashes. … Then holding up the U.S. Constitution, he branded it as the source and parent of all the other atrocities,—‘a covenant with death, and an agreement with hell,’—and consumed it to ashes on the spot, exclaiming, ‘So perish all compromises with tyranny! ’And let all the people saw, Amen!’ A tremendous shout of Amen!’ went up to heaven in ratification of the deed. …

4. Abraham Lincoln Speaks at Peoria, Illinois (1854)

In 1854, Abraham Lincoln, then a lawyer in Illinois, spoke out against the Kansas-Nebraska Act as a representative of the newly forming Republican Party.

[The Kansas-Nebraska Act] is the repeal of the Missouri Compromise. … I think, and shall try to show, that it is wrong; wrong in its direct effect, letting slavery into Kansas and Nebraska—and wrong in its prospective principle, allowing it to spread to every other part of the wide world, where men can be found inclined to take it.

This declared indifference, but as I must think, covert real zeal for the spread of slavery, I can not but hate. I hate it because of the monstrous injustice of slavery itself. I hate it because it deprives our republican example of its just influence in the world—enables the enemies of free institutions, with plausibility, to taunt us as hypocrites—causes the real friends of freedom to doubt our sincerity, and especially because it forces so many really good men amongst ourselves into an open war with the very fundamental principles of civil liberty—criticizing the Declaration of Independence, and insisting that there is no right principle of action but self-interest.

Before proceeding, let me say I think I have no prejudice against the Southern people. … When southern people tell us they are no more responsible for the origin of slavery, than we; I acknowledge the fact. When it is said that the institution exists; and that it is very difficult to get rid of it, in any satisfactory way, I can understand and appreciate the saying. I surely will not blame them for not doing what I should not know how to do myself. If all earthly power were given me, I should not know what to do, as to the existing institution. My first impulse would be to free all the slaves, and send them to Liberia,—to their own native land. But a moment’s reflection would convince me, that whatever of high hope, (as I think there is) there may be in this, in the long run, its sudden execution is impossible. If they were all landed there in a day, they would all perish in the next ten days; and there are not surplus shipping and surplus money enough in the world to carry them there in many times ten days. What then? Free them all, and keep them among us as underlings? Is it quite certain that this betters their condition? I think I would not hold one in slavery, at any rate; yet the point is not clear enough for me to denounce people upon. What next? Free them, and make them politically and socially, our equals? My own feelings will not admit of this; and if mine would, we well know that those of the great mass of white people will not. Whether this feeling accords with justice and sound judgment, is not the sole question, if indeed, it is any part of it. A universal feeling, whether well or ill-founded, can not be safely disregarded. We can not, then, make them equals. It does seem to me that systems of gradual emancipation might be adopted; but for their tardiness in this, I will not undertake to judge our brethren of the south.

When they remind us of their constitutional rights, I acknowledge them, not grudgingly, but fully, and fairly; and I would give them any legislation for the reclaiming of their fugitives, which should not, in its stringency, be more likely to carry a free man into slavery, than our ordinary criminal laws are to hang an innocent one.

But all this; to my judgment, furnishes no … excuse for permitting slavery to go into our own free territory. …

5. Abraham Lincoln Debates Stephen Douglas (1858)

While campaigning for the office of Senator from Illinois, Abraham Lincoln engaged in several debates with his opponent Stephan A. Douglas, the architect of the Kansas-Nebraska Act. Here is an excerpt of Lincoln’s speech in Ottawa, Illinois, on August 21, 1858.

… this is the true complexion of all I have ever said in regard to the institution of slavery and the black race. This is the whole of it, and anything that argues me into his idea of perfect social and political equality with the negro, is but a specious and fantastic arrangement of words, by which a man can prove a horse-chestnut to be a chestnut horse. [Laughter.] I will say here, while upon this subject, that I have no purpose, directly or indirectly, to interfere with the institution of slavery in the States where it exists. I believe I have no lawful right to do so, and I have no inclination to do so. I have no purpose to introduce political and social equality between the white and the black races. There is a physical difference between the two, which, in my judgment, will probably forever forbid their living together upon the footing of perfect equality, and inasmuch as it becomes a necessity that there must be a difference, I, as well as Judge Douglas, am in favor of the race to which I belong having the superior position. I have never said anything to the contrary, but I hold that, notwithstanding all this, there is no reason in the world why the negro is not entitled to all the natural rights enumerated in the Declaration of Independence, the right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. [Loud cheers.] I hold that he is as much entitled to these as the white man. I agree with Judge Douglas he is not my equal in many respects-certainly not in color, perhaps not in moral or intellectual endowment. But in the right to eat the bread, without the leave of anybody else, which his own hand earns, he is my equal and the equal of Judge Douglas, and the equal of every living man. [Great applause.]

… What is Popular Sovereignty? [Cries of “A humbug,” “a humbug.”] Is it the right of the people to have Slavery or not have it, as they see fit, in the territories? I will state-and I have an able man to watch me-my understanding is that Popular Sovereignty, as now applied to the question of slavery, does allow the people of a Territory to have slavery if they want to, but does not allow them not to have it if they do not want it. [Applause and laughter.] I do not mean that if this vast concourse of people were in a Territory of the United States, any one of them would be obliged to have a slave if he did not want one; but I do say that, as I understand the Dred Scott decision, if any one man wants slaves, all the rest have no way of keeping that one man from holding them.

… I ask the attention of the people here assembled and elsewhere, to the course that Judge Douglas is pursuing every day as bearing upon this question of making slavery national. … In the first place, what is necessary to make the institution national? Not war. There is no danger that the people of Kentucky will shoulder their muskets, and, with a  young nigger stuck on every bayonet, march into Illinois and force them upon us. There is no danger of our going over there and making war upon them. Then what is necessary for the nationalization of slavery? It is simply the next Dred Scott decision. It is merely for the Supreme Court to decide that no State under the Constitution can exclude it, just as they have already decided that under the Constitution neither Congress nor the Territorial Legislature can do it. When that is decided and acquiesced in, the whole thing is done.

Articles on Race from Scientific American

Some of your Wednesday Reports and in-class midterms asked questions about the impact of scientific theories on American ideas about race. To explore this question further, read the following articles from Scientific American:

- From the April 1, 1848, issue, read the article on “Human Hair.”

- From the February 21, 1852, issue, read the article on “The Aztec Children.”

- From the February 11, 1854, issue, read the article on “Agassiz on the Races of Man.”

Source: Making of America archive of Scientific American